Turkish Minority education in Western Thrace: A right or a security issue?

Turkish Minority Education in Western Thrace: A Right or a Security Issue?

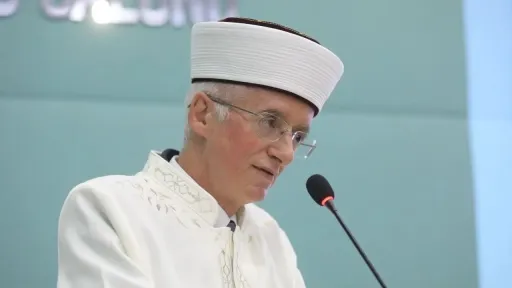

Ozan Ahmetoğlu, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the İskeçe (Turkish) Minority Secondary School and High School, wrote about the current situation and fundamental problems of Turkish minority education in Western Thrace.

The Turkish Minority in Western Thrace has a status recognized under international law, based on the education, religious, and cultural autonomy rights guaranteed by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. These rights are not only about “cultural diversity” but are essential for the preservation of minority identity and values.

IDENTITY AND CULTURE: THE CARRIER OF MINORITY EDUCATION

The Turkish mother tongue of the Western Thrace Turkish Minority is also a matter of identity. The Treaty of Lausanne granted the Turkish minority in Western Thrace the right to establish and manage their own schools and to receive education in their mother tongue. However, Greece has eroded and never fully implemented this right from the very beginning. None of the petitions submitted by minority institutions to establish minority schools providing Turkish-Greek bilingual education were accepted. Requests to open minority kindergartens offering both Turkish and Greek education, submitted to the Greek Ministry of Education with nearly all minority representatives’ signatures, were also rejected. Professional development requests for Turkish language teachers in primary schools were refused for years. Therefore, the right to education granted by the Treaty of Lausanne cannot be fully realized.

This right provides the essential foundation for maintaining linguistic, cultural, and religious existence. Having an autonomous education system as a minority and preserving identity and cultural diversity through Turkish education is evident. Minority schools and Turkish-language education are the institutionalized form of this right. The erosion of the “Autonomous Minority Education,” whose status is established by agreements, will gradually lead to the disappearance of this right guaranteed by international law.

During the discussion of the petition I submitted to the European Parliament Petitions Committee in 2019 regarding the lack of bilingual minority kindergartens offering Turkish and Greek education in Western Thrace, I vividly remember Greek MPs approaching the issue not from an educational rights perspective but from a perspective of denying the national identity of the Turkish minority, basing their arguments on prejudices and stereotypes. Unfortunately, this mindset still prevails in our country.

Despite the explicit provisions of the Treaty of Lausanne, Greece has not included kindergartens within the minority education system under compulsory education and continues to refuse Turkish mother-tongue education requests, putting children at a disadvantage from the very beginning. This is not just an educational issue but also a matter of identity and democracy.

Systematically obstructing Turkish education, or restricting it when obstruction is not possible, and continually eroding the rights and status of minority education and schools have unfortunately become state policy. The Greek state attempts, under extraordinary justifications, to practically eliminate the right to education.

At this point, I cannot ignore the building problem of the İskeçe Minority Secondary School – High School, which, despite having more than 700 students a few years ago, still operates in a century-old former tobacco warehouse. This event alone is enough to understand the approach to Turkish minority education in Western Thrace.

The İskeçe Minority High School building, originally constructed as a tobacco warehouse in the late 19th century and later converted into a school, is extremely old and far from a modern school appearance. When the student population exceeded 700 in 2019, the İskeçe Secondary Education Directorate implemented a two-shift education system (morning and afternoon) at the school. Students and parents went on strike twice, demanding a new school building and an end to the double shifts, but their requests have not been accepted by the state to this day. The mindset that considers a modern school building excessive for a minority school with hundreds of students alone reflects the attitude toward minority education. This approach has never “accepted” minority education or schools and sees them as a “foreign” element within the state’s body.

ADMINISTRATIVE INTERVENTIONS

Another issue that has become noticeable in recent years is the administration of minority schools: the boards of trustees, elected by parents every three years, are being rendered ineffective. The powers and areas of activity of the boards are restricted and obstructed. In some cases, even entering the school is restricted for board members, who are legally the administrators of the schools. The Greek approach to minority schools is still framed as a “security” issue. Education ceases to be a democratic space and becomes a domain of control.

WHAT DOES INTERNATIONAL LAW SAY?

The Treaty of Lausanne (1923) explicitly grants minorities the right to education in their mother tongue (Articles 37-45). UN and European conventions also guarantee the right to education and non-discrimination.

POLITICAL AND SECURITY-ORIENTED APPROACH

Looking at Greece’s official statements and practices, the education issue in Western Thrace is perceived almost entirely as a security concern. Excessive precautionary measures in minority schools are not applied elsewhere. This mindset is concretely reflected in the following practices:

- Closure of schools and central control over teacher appointments in primary schools.

- Continuous rejection of minority kindergarten requests.

- Refusal of Turkish language seminar requests for teachers in primary schools.

- Keeping schools under strict control. Board members of schools, who are administrators, have limited access. Visits to minority schools require written permission from competent authorities days in advance.

A democratic state, on the other hand, should maximize rights, ensure transparent administration, and adopt a multicultural approach.

The goal regarding education and schools, which are one of the foundations of society, is not only to “keep schools open.” The minority’s right to establish, manage, and receive education in their mother tongue is recognized under Lausanne and international law. Current practices create inequality in education, weaken identity, violate cultural rights under the pretext of security, and impose intense supervision and self-control on personnel.

WHAT COULD BE THE SOLUTION?

- The minority’s educational autonomy should be restored in line with Lausanne and ECtHR obligations.

- Minority kindergartens offering Turkish and Greek education should be opened.

- Democratic transparency and tolerance, instead of a security-oriented perspective, should prevail in administration.

- Legislative improvements in the management of minority education and schools should be made in consultation with minority institutions.

Let us not forget: education among the Turkish Minority in Western Thrace is not merely a cultural right but a cornerstone of a democratic society. The problem in Western Thrace is more than education: it is a test of identity and democracy.

[Ozan Ahmetoğlu is Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the İskeçe Minority Secondary School and High School and a staff member of Gündem newspaper. His writings mainly focus on the educational issues of the Turkish Minority in Western Thrace.]

Note: This article was first published in the August 2025 issue of İnsicam Magazine’s “Western Thrace File.”