On the silent but determined struggle of identity, faith, and dignity in Western Thrace

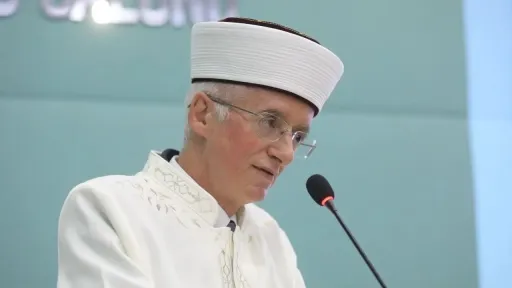

Exclusive Interview with Mustafa Trampa, Mufti of İskeçe and Chairman of the Advisory Board of the Turkish Minority in Western Thrace

Interview: Cengiz Ömer

The Muslim Turkish Minority in Western Thrace, which has been struggling to survive for over a century, demonstrates a unique resistance in preserving both its faith and identity. Their struggle is sometimes visible through a legal defense petition in courtrooms, and sometimes through a silent crowd walking the streets of İskeçe and Gümülcine.

The Western Thrace Turkish Minority, striving to exist with its Turkish and Muslim identity, resists Greece’s denialist policies and the world’s indifference with faith and dignity, through a peaceful but determined struggle.

One of the prominent figures at the forefront of this struggle is Mustafa Trampa, Mufti of İskeçe and Chairman of the Advisory Board of the Turkish Minority in Western Thrace. We spoke with him about the voice, hopes, and resistance of a people in these ancient lands who are being silenced…

Interviewer: Mr. Trampa, thank you for honoring us by accepting this interview invitation.

We would like to discuss not only your personal journey but also the conditions of the Turkish Minority in Western Thrace and the struggle for identity and faith in this region. With your permission, let us begin with our first question:

Q: Mr. Trampa, could you briefly introduce yourself for those who do not know you? Under what conditions were you raised?

A: I was born in 1974 in Şahin village, a part of İskeçe. After completing primary school in my village, I graduated from Edirne Imam Hatip Secondary and High School in 1993. Then I went to Turkey and completed my undergraduate education at the Faculty of Theology, Selçuk University in Konya, in 1998. Later, I completed my master’s degree at Üsküdar University, Institute of Sufism Studies, with a thesis titled “The Mawlid Tradition in Western Thrace.” I am currently continuing my doctoral studies in Islamic Sufi Philosophy at Istanbul Sabahattin Zaim University.

Throughout my education, I had the opportunity to develop myself both in religious sciences and social awareness. Growing up in Western Thrace means not only pursuing education but also carrying the responsibility of standing strong with your Turkish and Muslim identity. I was raised with this awareness.

Q: As a Turkish and Muslim of Western Thrace, how do you define your identity?

A: Being a Turk of Western Thrace means carrying the responsibility of a historical and faith-based belonging. As a minority whose rights are guaranteed by international agreements, especially the Treaty of Lausanne, we strive to preserve our Turkish identity, language, religion, and culture. Being Muslim is the cornerstone of this identity. Protecting our religious values, performing our worship freely, and passing them on to future generations is existential for us.

Q: How is the Turkish Minority in Western Thrace struggling to exist today? What are the main points of this struggle?

A: The Turkish Minority in Western Thrace is a community whose identity is not recognized, whose educational and religious freedoms are restricted, and whose right to association is violated. Our fundamental struggle is the official recognition of our “Turkish” identity. Additionally, in accordance with international law, including the Treaty of Lausanne, bilateral agreements, the EU acquis, and the UN Declaration of Human Rights, the election of muftis, the autonomy of minority schools, the quality of Turkish-language education, and the protection of our youth’s rights are also key aspects of this struggle.

Q: How do you observe the assimilation policies implemented by the Greek state? What are the most prominent examples?

A: Assimilation policies have been present in various forms for many years. Examples include the state arbitrarily appointing muftis, ignoring the Lausanne and Athens Agreements and international law; closing associations carrying the name “Turkish”; restricting minority education; and attempting to bring our religious institutions and life under state control through forced appointments of mosque imams and deputy muftis. Even today, if the word “Turkish” is banned on association signs, it is a direct denial of identity.

Q: What role do the Mufti Institution and Advisory Board play in this struggle?

A: Our mufti offices are not merely religious authorities; they also represent the historical memory and resistance of the community. As elected muftis, under the rights granted to us by bilateral agreements and international law, we reflect the religious will of the people and protect freedom of belief. The Advisory Board serves as a civil and legitimate representative platform aimed at creating common understanding on the collective issues of the Turkish Minority in Western Thrace. We strive to resolve our community’s problems through peaceful means and ensure solidarity among our institutions.

Q: As Mufti of İskeçe, how do you assess the current state of religious life in the region?

A: Despite everything, religious life in Western Thrace remains vibrant. Our mosques are full, and our youth remain closely attached to their religious identity. Of course, we face various restrictions, but the community’s dedication to its faith and support for the elected muftis and imams keep religious services alive. This motivates us both spiritually and institutionally.

Q: What kind of pressures do you face regarding religious education, mosques, imams, and the community’s religious life?

A: In recent years, the Greek state has attempted to control the religious sphere. Particularly, Law No. 3536/2007 established a “religious personnel training” system under state control. This law defines imams as public officials, aiming to detach them from the people and the mufti offices. Gradually, state-trained and appointed religious personnel replaced qualified individuals recommended by the community and muftis, who adhere to religious traditions. This system effectively blocked the appointment of qualified religious personnel who graduated from Imam Hatip schools or received theology education in Turkey. Priority was instead given to graduates of special state-run imam training programs.

As elected Muftis and the Advisory Board, we have consistently emphasized that religious leaders should be chosen according to the faith, tradition, and preferences of the community. The state’s refusal to recognize this constitutes a clear pressure mechanism from our perspective. International institutions also report that these practices violate religious autonomy in Greece. The pressures we face are not limited to the appointment of mosque imams; they directly threaten the community’s right to religious freedom and to practice its faith.

Q: How do historical, cultural, and emotional ties with Turkey affect the sense of existence among Western Thrace Turks?

A: Turkey is not just a state for us; it is the name of a heartfelt connection. Our language, religion, traditions, and history are deeply intertwined with Turkey. Of course, we are citizens of Greece and respect this country. Yet, the historical ties that shape our identity serve as a spiritual source of strength, especially in difficult times.

Q: If you had a message for the public in Turkey, what would you like to say on behalf of the Western Thrace Turks?

A: A handful of Muslim Turks in Western Thrace strive to preserve their identity despite all pressures. The sensitivity of the Turkish public to this struggle reminds us that we are not alone. Knowing that you stand with us through your prayers and support strengthens our resistance. Please do not forget your brothers and sisters in Western Thrace.

Q: Mr. Trampa, thank you very much for this meaningful and sincere conversation. Your words are invaluable both for our readers and for all Turkish and Muslim communities. Lastly, what is your message to the Muslim Turkish youth in Western Thrace and to readers in Turkey?

A: I thank you for giving us the opportunity, through your magazine, to reach the Turkish public and tell the story of our brothers in Western Thrace. To our youth, I say: Uphold your identity, religion, and language. Every step you take in Western Thrace is part of a resistance. To our brothers and sisters in Turkey, I say: We stand tall here not only for ourselves but for all Turks and Muslims. Be the voice and prayer of this struggle.

Closing:

Being Turkish and Muslim in Western Thrace is not merely about preserving an ethnic or religious identity; it is about keeping alive a memory, a language, a faith, and a stance. Mustafa Trampa’s words are a conscientious and determined representation of a struggle that continues quietly but with dignity in this land.

This struggle does not always make headlines; often, it is ignored. Yet, the minority community continues to defend its identity and rights through peaceful walks and actions, whether in courtrooms, on mosque pulpits, or in public squares. It is a watch of truth maintained with faith, persistence, and hope.

The Turkish Minority in Western Thrace continues its existence with justice, patience, and faith amidst invisible pressures and unheard cries. For them, to exist is more than a choice—it is a responsibility they carry as a trust.

We see it as our duty to amplify this voice and make this resistance visible, because this struggle is not only the conscience test of Western Thrace but of the entire Turkish and Islamic world.

Note: This interview was first published in the August 2025 issue of İnsicam Magazine.